Determining educational placements for students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is challenging, as those involved attempt to balance philosophical beliefs, legal requirements, evidence-based practices, and the individualized needs of each student. Though successful and meaningful involvement in general education settings is often the ultimate goal and a socially important aim for parents and professionals, many students with ASD are served in more restrictive settings on the service continuum. Due to the heterogeneity of students on the autism spectrum, the level and intensity of services required, the desire for individualized intervention, or the lack of community support for inclusive placements, students with ASD may be educated partially or completely in special education settings.

It is likely that in more segregated settings, in an effort to ensure a low student to staff ratio, that a number staff members, including teachers, therapists, and paraprofessionals, will interact with the students. As the number of paraprofessionals working with students with ASD continues to rise (French, 2003), teachers are faced with the challenging task of coordinating the varied schedules of numerous staff members, as well as their students. Recent statistics show that 75% of special educators supervise one or more paraprofessionals (French, 2001), while receiving little training in the management or organization of additional classroom staff. As staff numbers grow, the role of classroom teachers shift to that of a “planner, director, monitor, coach, and program manager” (French, 1999, p. 70).

The role of a supervisor may be overwhelming to teachers in the autism field, as they struggle to meet the complex needs of their students, facilitate effective inclusive programming, respond to the requests of families and administrators, and attempt to stay informed of empirically validated educational practices. In balancing these demands, providing daily instruction, guidance and direction to classroom staff may not be prioritized or feasible. Giangreco and Broer (2005) found that paraprofessionals received less than 2% of a special educator’s time in training, supervision, or professional guidance.

One solution to the coordination and supervision challenge is the use of schedules for both staff members and students. The use of schedules for students and educational personnel contributes to the development of a structured and comprehensible classroom environment—a vital component of effective programming for students with ASD (Iovannone, Dunlap, Huber, & Kincaid, 2003). Providing an overall schedule for adults and students allows all classroom members to predict what is currently happening and what will happen next. This overall schedule outlines the events of the day, lets teachers know who they are responsible for, and how staff members are being used. The framework outlines who, what, where, and when.

The first step in designing this framework is to plan the schedules of the individual students. While this process may be time intensive initially, it will greatly reduce the supervisory challenges throughout the school year. The South Carolina Department of Disabilities and Special Needs developed seven steps to utilize when planning an individual’s schedule (Boswell, Braswell, & Wade, 1997).

- Describe the individual: Consider age, setting, strengths, interests, needs, etc.

Kevin is 6 years old and is served primarily in a self-contained setting. He enjoys sensory and leisure activities, as well as music. He is non-verbal, yet is beginning to express his wants using pictures through choice making opportunities. He has a short attention span and benefits from 1:1 and small group activities with minimal distractions. - Divide the hours of programming into short blocks of time: 15 minutes is suggested but this is dependant on the age, attention span, and work skills of the student.

- Block out non-negotiable segments: This includes lunch, transportation times, etc.

- Pencil in “negotiables” with other people: Coordinate with therapists, peer helpers, inclusion settings, community outings, etc.

- Plug in, shift, and balance activities that reflect these key concepts:

- Balance of teaching/supervising

- Meaningful contexts (i.e., teach skills where it will likely be used, such as bathroom, eating area)

- Balance of preferred/non-preferred activities

- Balance of in-seat/movement activities

- Length of activities

- Productive use of “free time” (i.e., teaching appropriate leisure skills during breaks/choice times)

- Productive use of transitions (i.e., reducing the amount of time waiting between activities)

- Partial participation (i.e., allowing a student to watch during an activity or join an activity after it begins rather than participating as the other students do)

- Flexible grouping (i.e., grouping students in a variety of ways depending on the goal of the activity, such as student interest, attention span, communication skills)

- Review to ensure that generated schedule is addressing individual needs as determined by the IEP team: Individual schedule should change throughout the year as educational needs and priorities shift.

- Decide on individualized presentation of schedule: Discuss how the schedule information will be communicated to the student (i.e., concrete objects, photographs, line drawings, words).

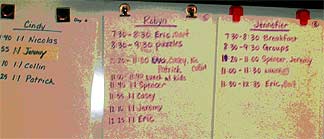

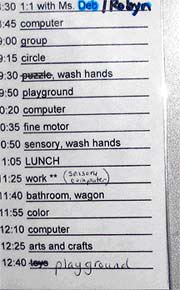

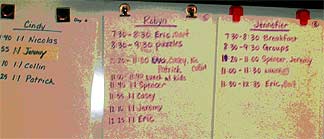

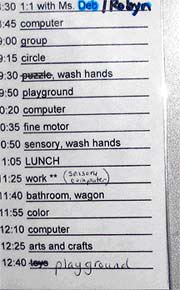

The next vital step is to plan for staff choreography and coverage. Following similar steps as those listed above, determine what staff member will be responsible for each student, curricular area, or classroom center for each time period throughout the day. Classroom teams may find several models of staff choreography helpful, including the “man-to-man” or “zone” systems (to borrow basketball defense terminology). Teachers may assign staff members to work with specific student(s) for periods of time (“man-to-man”), and the staff member will move with the student(s) to different activities or classroom areas. Or teachers may designate staff to specific classroom areas (i.e., the art table, a 1:1 teaching area, a leisure center) and students rotate through these centers (“zone”). It is helpful if the schedules for the adults and students are posted conspicuously each day so all personnel can easily see where each student and staff member should be (see example 4 and 5).

Example 1

Elementary Student Schedule

| Kevin’s Schedule-Monday | |

| 7:45-8:00: Bathroom, Breakfast | Addressing adaptive skills in meaningful context |

| 8:00-8:15: Sensory | |

| 8:15-8:35: Circle, Wipe table/trash out | |

| 8:35-8:50: Work, Kevin’s Choice | Balance of non-preferred/preferred |

| 8:50-9:05: Work with Staff 1 | |

| 9:05-9:15: Group work | Balance of seated/movement |

| 9:15-9:35: Playground | |

| 9:35-10:00: Work, Kevin’s Choice | Productive use of free time during choice |

| 10:00-10:20: Speech with SLP | “Negotiable” with the speech therapist |

| 10:20-10:25: Sensory | Balance of teacher directed/student directed |

| 10:25-10:40: Music group | Grouping with non-disabled peers |

| 10:40-10:50: Free Choice | |

| 10:50-11:00: Story | Partial participation (joins story for last part) |

| 11:00-11:45: Cafeteria, Playground | Lunch time is a non-negotiable |

| 11:45-12:00: Sensory, Bathroom | |

| 12:00-12:25: Work, Kevin’s Choice | |

| 12:25-12:35: Group work | Flexible grouping (not all students participate) |

| 12:35-1:00: Work with Teacher | |

| 1:00-1:10: Art | Activities range from 10-25 minutes |

| 1:10-1:35: Work, Kevin’s Choice | Frequent opportunities for choice |

| 1:35-1:45: Music, School Bus | |

Example 2

“Man-to-Man” Adult Schedule for Elementary Setting- 8 students, 1 teacher, 2 paraprofessionals.

ADULT SCHEDULE-MONDAY

Teacher

8:15: Circle

8:35: Kevin wipe table/trash out

9:00: Work with Joseph

9:35: Work with William

10:00: Work with Karl

10:20: Music group

10:40: Story

12:15: Work with John

12:35: Work with Kevin

1:00: Art

1:35: Closing | Staff 2

8:30: 1st grade with Sean

9:00: Library

9:55: Reading group

10:15: Wagon with Joseph

12:10: Work with Catherine

12:30: Work with Sean

Speech Therapist

8:35: Work with Karl

9:00: Work with Catherine

9:35: Work with Sean

10:00: Work with Kevin |

Staff 1

8:40: Swing William

8:50: Work with Kevin

9:00: Library

9:35: Work with Karl

12:15: Attendance with Sean

12:30: 2nd grade with Joseph | Other

Library with 1st grade 9-9:30

Peer helpers: 10:20-11:00

Group Work

Gears

Puzzles

Stringing/Lacing |

Example 3

“Zone” Adult Schedule for High School Setting- 8 students, 1 teacher, 2 paraprofessionals, 1 career coach.

| 9:00-9:20 | Domestic Center with 2 students (A,B) | Oversee break/independent work of 2 student (C,D) | Out with 1 student at school job (E) | Group area with 3 students (F,G,H) |

| 9:20-9:25 | Students rotate/staff helps with transition | | | |

| 9:25-9:45 | Domestic Center with 2 students (C,D) | Office Center with 2 students (G,H) | Oversee 1 student in break area, help take apart/set up materials in centers (F) | Group area with 3 students (A,B,E) |

| 9:45-9:50 | Students rotate/staff helps with transition | | | |

| 9:50-10:10 | Domestic Center with 2 students (E,F) | Office Center with 2 students (C,D) | Oversee break/independent work of 2 students (A,B) | Leisure Center with 2 students (G,H) |

| 10:10-10:15 | Students rotate/staff helps with transition | | | |

| 10:15-10:35 | Domestic Center with 2 students (G,H)-Water Plants On Campus | Office Center with 2 students (A,B)-Deliver Office Materials to Teachers | Oversee break/independent work of 2 students (E,F) |

Example 4

Posting adult schedules on board.

Example 5

Posting student schedule near student’s area (for adult referencing—student use picture cues to direct him to scheduled areas).

A structured learning environment allows students with ASD to make sense of what is happening, as well as the staff members responsible for their instruction and learning. When assessing the structure of a classroom, Olley and Reeve (1997) recommend observing in a classroom for 10 minutes in an effort to identify what each student is supposed to be doing. If the observer is unclear about the activity, goal, or curricular area, it is likely the student is unclear as well. Extend this observation to the activities of the staff members—is it clear what/who each staff member is responsible for? Again, if the observer is unable to identify the duties of each staff member, classroom choreography is an issue to be addressed.

Tips for Implementation:

- It is beneficial to create the schedule frameworks with the classroom team members and to take time to revise and restructure the schedules as the needs of the students and staff members change throughout the year.

- Building flexibility and opportunities for generalization within the schedules is important. To encourage students with ASD to become more flexible and transfer skills to different settings/staff members, it is important to build variety into each daily schedule—including different activities throughout the day/week, working with a number of staff members, and working in a number of different settings.

- These strategies and steps can be easily adapted to schedule paraprofessionals and other staff members in all educational settings, including inclusive environments, therapy settings, and community-based programs.

Questions for staff to consider when planning classroom and individual schedules (Boswell & Cox, 1999):

- Is the schedule clearly outlined so teachers know all daily responsibilities?

- Is there a balance of individual, independent, group, and leisure activities throughout the day?

- Do individual schedules consider student needs for break times, reinforcement, non-preferred activities followed by preferred?

- Does the schedule help a student with transitions- where to go and what to do?

- How are transitions signaled (timer, visual cue, student monitors clock)?

- Is the schedule represented in a form easily comprehended by the student?

References

Boswell, S., Braswell, B., & Wade, C. (1997). Designing programming for people with autism: Designing daily schedules. Columbia, SC: South Carolina Department of Disabilities and Special Needs Autism Training Division.

Boswell, S., & Cox, R. (1999, May). Choreography of the classroom. TEACCH® Level 2 Seminar, Chapel Hill, NC.

French, N. (1999). Topic #2 Paraeducators and teachers: Shifting roles. Teaching Exceptional Children, 32, 69-73.

French, N. (2001). Supervising paraprofessionals: A survey or teacher practices. Journal of Special Education,35, 41-54.

French, N. (2003). Paraeducators in special education. Focus on Exceptional Children, 36, 1-15.

Giangreco, M. & Broer, S. (2005). Questionable utilization of paraprofessionals in inclusive schools: Are we addressing symptoms or causes? Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20, 10-26.

Iovannone, R., Dunlap, G., Huber, H., & Kincaid, D. (2003). Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 150-166.

Olley, J. G., & Reeve, C. E. (1997). Issues of curriculum and classroom structure. In D. J. Cohen & F. R. Volkmar (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders.(2nd ed., pp. 484-508). New York: Wiley.

Hume, K. (2005). Classroom choreography: The art of scheduling staff and students. The Reporter, 10(3), 15-19.